This is an oversimplified story of why the UK left the first European Exchange Rate Mechanism, and probably why they didn’t later bother with the euro.

What was the ERM?

The original European ERM (now called “ERM I”) was like a beta version of the current multinational euro currency/system that ran until 1999. For all practical purposes under the ERM then, each country still retained their own national currency, i.e. Germany still used the deutsche mark, France the franc, Spain the peseta, Italy the lira, etc.

But to give (some) effects of “a single currency”, the governments of these countries have agreed that the exchange rates between the currencies should legally more or less stay constant. It’s not exactly constant - countries, depending on their level of commitment and abilities, are allowed to fluctuate within defined upper and lower bounds.

So while this system does not guarantee the elimination of exchange rate risk for cross-border commerce, this system at the very least meant that in theory, this risk has legally binding worst and best case scenarios. But more importantly at that time, this system was a politically palatable stepping stone to test out this new ever closer economic relationship amongst European countries - nominally, each currency was still its own currency, with their own heritage and collective cultural memories attached and and all that (which would appeal to the “we are proudly unique, and want to stay sovereign” voters). But ultimately, they should be as equally fungible as each other, and is a signal to the world that Europeans are one big happy family (which would appeal to the voters in favour of some form of unification).

What does the UK have to do with it?

The Conservative party was split between those who wanted to be closer to Europe, and those who didn't. The then prime minister Margaret Thatcher (perhaps as an attempt at appeasing those in favour) brought the British pound into the ERM in October 1990, at an exchange rate of 2.95 deutsche marks to a pound (she was replaced in November anyway). The pound was allowed to fluctuate at a 6% band.

So, why didn’t the UK stick around?

It wasn’t for the lack of trying. It was probably uneconomical to do so, but it certainly was going to be extremely politically detrimental to whoever was in charge of running the country had they chosen to.

Why?

Let us participate in a few simple thought experiments. The list here may look at first like a collection of disjointed and unrelated things, but I promise to bring it all together again and you’ll hopefully come to appreciate the reason the UK ditched the ERM.

Some simple thought experiments

First, imagine if your job is to control economic growth, and your only tool available is to move interest rates up and down. In theory, if you wanted to encourage people to spend money (and hence, grow the economy), you’d probably want to set interest rates low. This would mean savers would have less of an incentive to keep their money in the bank, and they would take it out and spend it. Also, this may also lead to cheaper loans, so some people would borrow and spend that additional money.

But on the flip side of this same coin, let’s say that your low interest rate environment has encouraged excessive spending to the point where there’s too much money chasing too few goods. Given your only tool of interest rates, you might feel inclined to increase the interest rates so that some of the excess money is taken out of immediate circulation - more have more of an incentive to save their money in a savings account, and fewer and smaller loans are taken as they become less affordable.

Now, imagine that you are a savvy saver - you always know which are the best savings accounts that offer the best interest rates. But let’s say that the current best interest rate available is 0.0000001%. This may not be worth your while. But then you realised that a savings account in another country (in their own currency) offers an interest rate of 5%. What you can choose to do then is to sell your currency for the other currency, and deposit that money in the other bank. The act of selling your currency to buy the other drives the exchange rate to reflect the relative demand - your currency goes down, and the other goes up. (It is this very type of trade that spawns the stereotype of “Mrs Watanabe”. Because interest rates in Japan are so rock bottom, there is a large retail demand for foreign currency accounts that pay the much higher foreign interest rates. The retail banks in Japan are more than happy to oblige)

These scenarios, in isolation, look very contrived. Some of you might even go “duh, it’s so obvious”. So let’s put this all together then.

Confluence of different economies

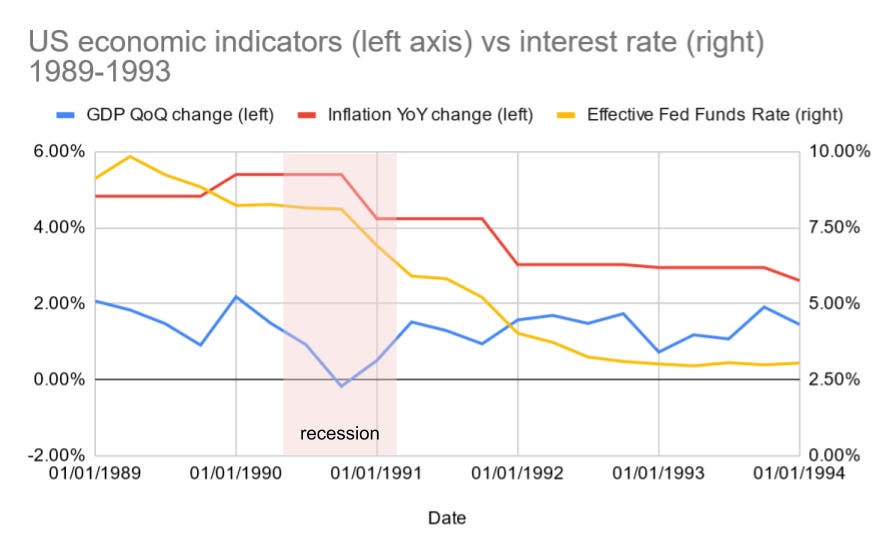

So you see, the modern world’s superpower, the United States, was just coming out of a recession in the early 90’s (pink area in Figure 1 below). You can see that economic growth was abysmal (blue line). So, based on the steps established in the section above, if you had control on interest rates, what should you do to encourage economic activity? That’s right! You lower interest rates! And lower interest rates they did (notice the yellow line trending downwards).

Figure 1 - US economic indicators versus interest rate response from 1989 to 1993. (Sources: St Louis Fed)

Similarly, the UK was experiencing a recession during this period (pink area in Figure 2 below). Its economic growth (blue line) was worse than that of the US, both in terms of its depth and duration. Again, if you only had controls to the interest rate lever, what does your impulse tell you to do? That’s right! You would want interest rates to go down to get people spending money again and to rebuild your economy! (And to be fair, your current interest rate of 10% seems pretty high already!)

Figure 2 - UK economic indicators versus interest rate response from 1989 to 1993. (Sources: Office ofNational Statistics, Bank of England)

But wait! Remember that the UK signed an agreement to keep exchange rates more or less constant with the German deutsche mark. It’s a legal agreement! You generally want to keep your promises with your neighbours, otherwise, it’s kind of a bummer. And if you reduced your interest rates, you may end up lowering the value of the pound so much that you might break your promise. You don’t want that to happen, right?

But you know what? What if Germany could reduce its interest rates too? If we did it together, our relative interest rate movements would be zero, and the UK wouldn’t need to break its promise on the exchange rate!

Wow, sounds like a brilliant idea! Let’s go ask Germany if they’d like to join us!

Figure 3 - German economic indicators versus interest rate response from 1989 to 1993. (Sources: St Louis Fed, Bundesbank, inflation.eu)

You take a look at Germany’s economic growth, and it looks like they are in a recession too (blue line in Figure 3 above)! But wait, what have they done?

You find out that West and East Germany are getting back together again. But because the job opportunities in western Germany are so much better paid, many east Germans move over to the west to work. This has resulted in such a large brain drain that eastern German industrial output has fallen by 46% after just 6 months of economic reunification (link to paper co-authored by Janet Yellen in 1991).

As a result, the German federal government has the incentive of spending a lot of money to try to bring the quality of life in eastern Germany up to par with that of the west. This also means that the German government has the incentive to allow the 1:1 exchange of the old East German currency with the deutsche mark (because how else are you going to look them in the eye and tell them, “brother, from now on, we’re equal partners again”?).

However, the Bundesbank (the German central bank), fears that this exchange rate will mean a giant whopping sudden increase in the total amount of money in the German economy. That’s not to mention the additional spending that the government wants to do as transfer payments. The central bankers were shook. This may lead to runaway inflation!

So what did the Bundesbank do? In the midst of a weakened global economy, they decided that inflation was the more important of the problems to solve. And central bankers then (and maybe now) have only one very very blunt tool to use - they increased interest rates.

The result? The deutsche mark rose in value / the pound dropped in value. Now, the only way for the UK to maintain the legally allowed lower bound of exchange rates was to increase its interest rates. But as we have established earlier in this section, that’s probably not what the UK economy needed at that time. Imagine being the politician in charge, and you would have to tell your voters that you chose to increase interest rates so that another country (Germany) could advance its policies at the cost of a chance at economic recovery when it needed a shot in the arm the most.

And that is why, at least on a political level, why the UK left the ERM.

N.B. The UK did try to raise the interest rate twice on the very same day (from 10% to 12% to 15%), but then decided that it was just not politically viable.

Also, the Swedish did increase their interest rates. The 1-week STIBOR rate went up to 90% on 16 September 1992:

Figure 4 - Swedish interest rates, with a peak of 90% on 16 September 1992. (Source: Riksbank)