Flamingos, banks as arms of the state, European banks and credit standards, gig workers

Your dose of nonsense - Thursday, 05 November 2020

If you liked this, consider liking, subscribing and forwarding. You know, for the algos. If you didn’t like it, consider forwarding it to someone you don’t like.

Source: Getty Images via the BBC

Source: Pedros Szekely via Mental Floss

Source: Martin Mere Wetland Centre

Banks are an arm of the state

You see, modern banks are these weird non-governmental yet very governmental organisations. Sure, many banks are owned by public shareholders with little to no government ownership (let’s ignore state-owned banks for now). Yet, everything they do technically has to first be blessed by the regulators and government officials - the authorities tell you what you can and cannot do, and as long as you play within this sandbox, you’re fine to roam around. Otherwise, say goodbye to your banking license.

There’s also one more special property that banks have - it’s one thing that banks do for the government (as opposed to being able to choose what you can do from an allowed list). And that thing is to help the government control the flow of money in the economy.

How does that work? Well, it’s called fractional reserve banking - to put it very simply, it’s how modern money is created. When you deposit £10 in your bank account, your bank can choose to lend that £10 out to someone else, and suddenly you have a total of £20 in the system (you have £10 listed in your bank statement, and so does the other person who has borrowed £10 from the bank. It’s like creating money out of thin air!)

But you see, the power to create money legally lies with the state, hence that is why banks, while they may be public-listed companies, are arms of the state. And that is partly why it is so hard to get a banking license - the government is sort of deputising its power to create money to these banks.

So, how does the government use the banks to control the flow of money? Well, in the good times, the government might want to dial the flow of money in the economy down a notch, just in case things get a little too spicy. Using the £10 example above, the government might tell the banks that it can only lend out £4 of that £10, and they would have to keep that £6 fraction as reserve (the “fractional reserve” bit of fractional reserve banking). Hence, there would only be £14 in the system.

If the economy cools down, the government might want to spice the flow of money up by telling the banks that they only have to maybe keep £2 as reserve, hence the system would have £18. And the banks have all the business incentive in the world to lend out every available penny - cash that is sat in the reserve is simply wasted business opportunity.

However, this is where the relationship gets weird and breaks down - when a government wants to increase the flow of money to stimulate the economy in a really really bad economic condition, they can tell the banks to lend as much money as they want. But when economic conditions are just so bad, the banks may just choose to not lend that money. Sure, the banks are doing the work of the state, but they are still ultimately answerable to their shareholders. They would rather not lend that money out (and forgo business opportunities) and preserve the shareholders’ capital (because they think that most of these opportunities would lead to default anyway).

And it’s at this point where the government, or in the EU’s case, the European Central Bank starts charging banks for the reserves that they have via negative interest rates to motivate banks to lend out the reserves. But you know, sometimes they think that they rather pay the ECB money than to lose money on their perceived potential for defaults if they lent it out.

European banks have tightened their credit standards

In other words, European banks just aren’t too keen to lend money now.

According to the third quarter euro area bank lending survey run by the European Central Bank, European banks have further tightened their lending standards this quarter over the last. These were the types of loans that were surveyed:

Loans to enterprises;

Loans for home purchases; and

Consumer loans (e.g. personal loans).

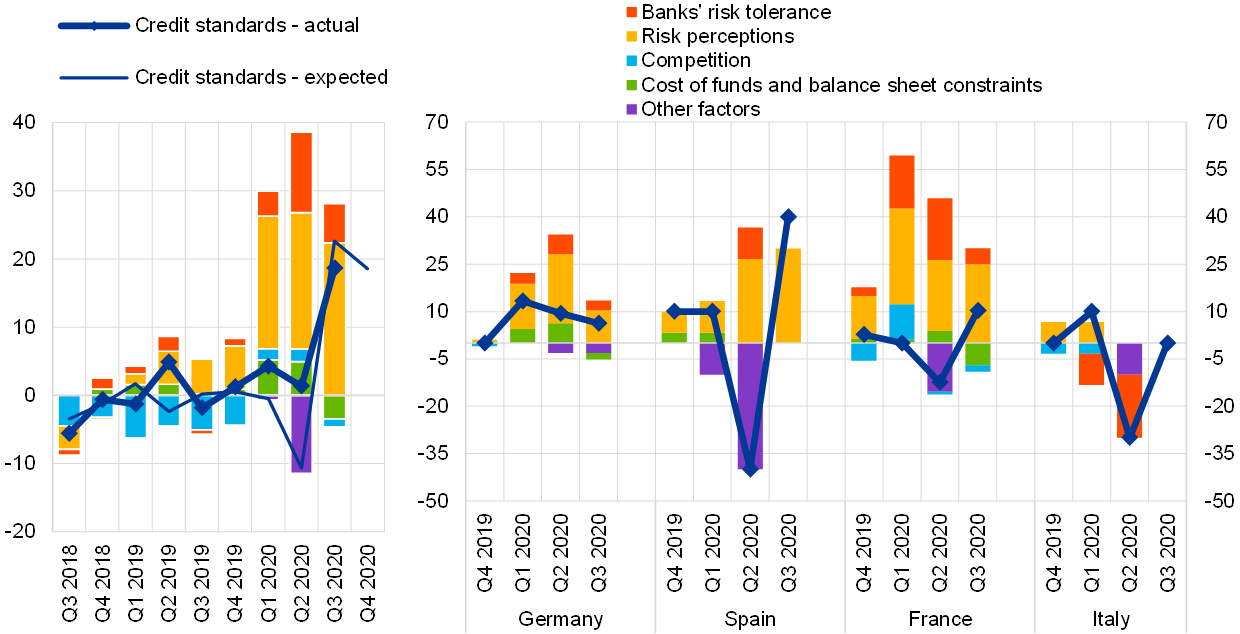

Here’s the plot for the change of credit standards for loans to enterprises (anything above 0 means it’s a positive change from the last period):

Source: ECB

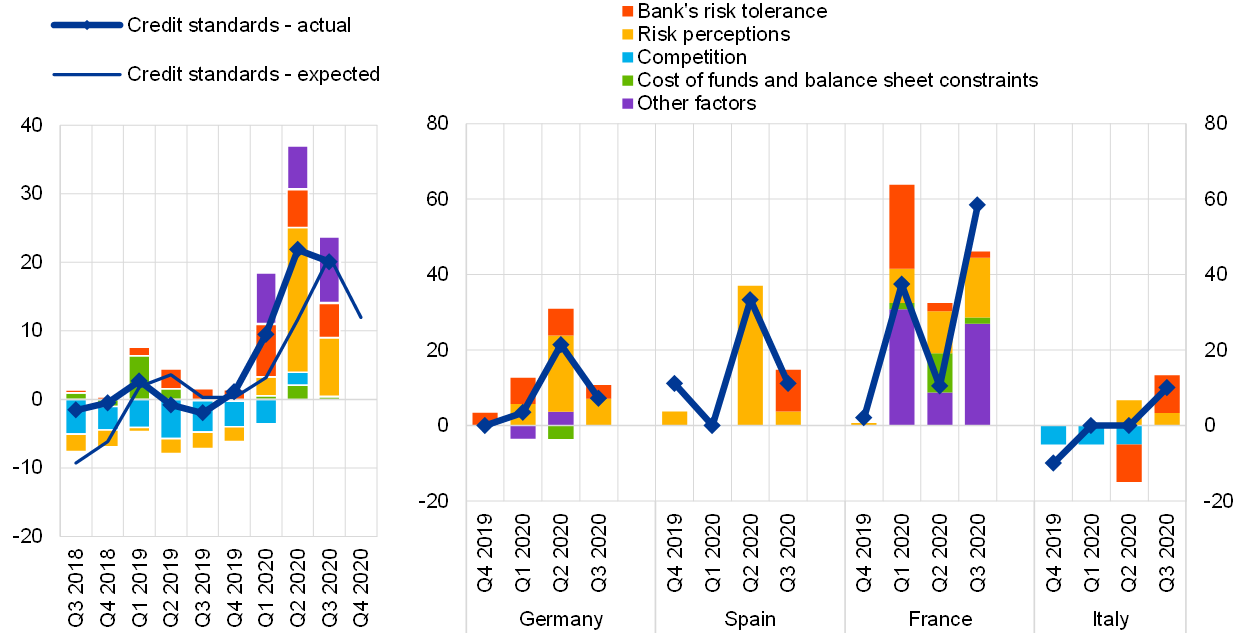

Here’s the plot for loans for home purchases:

Source: ECB

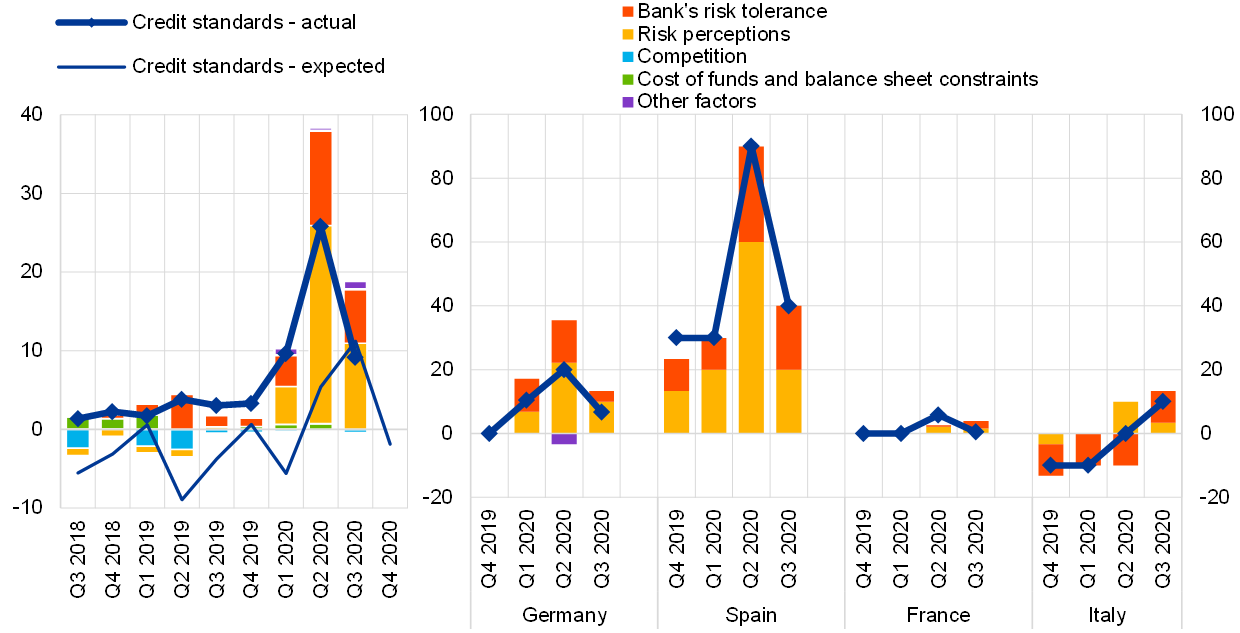

Here’s the plot for consumer credit:

Source: ECB

So, if banks are a bit skittish to help the government create that flow, what can a government do? Well, they can always decide to directly pay its citizens’ bank accounts (and here is how we come to the whole Universal Basic Income debate).

The people have voted - gig workers are contractors, not employees

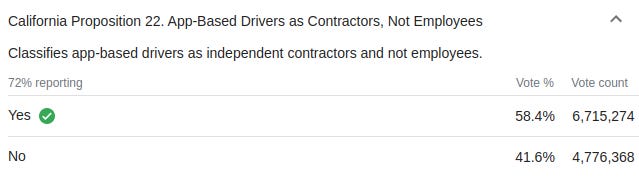

So yesterday, amongst other things to vote on, California voted whether to consider “App-Based Drivers as Contractors, Not Employees”. A “Yes” vote means that drivers for the likes of Uber or Lyft won’t get employee-level healthcare, minimum wages and other benefits (the ride hailing companies are going to give some benefits, and some level of “minimum wage”, just not the full blown stuff).

Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart and Postmates spent $205mil campaigning for this.

The result? 58.4% voted “Yes”.

Source: Google

I have no horse in this race, but, can someone please explain to me how does a state that consistently votes for a party since 1992, whose platform is currently all about:

Regulating Big Tech (Reuters);

Taxing Big Tech more (Biden’s tweet);

Empowering workers, including a $15/hr minimum wage (Biden’s campaign website)

also then choose to vote for Proposition 22?

PS: None of my content is sponsored content. All opinions are my own. Nothing in this newsletter is investment, legal, business, medical, or life advice (my subtitle is “Your daily dose of nonsense”). Don’t be believing everything a random guy on the internet says.