Knight: “Sire, the peasants are revolting!”

King: “Of course they are!”

“How do I find people to do all this work?”

Imagine if you will if there was somehow, I don’t know, a pandemic that is causing a labour shortage. Some say that it is self-evident then that any employer would have to offer much higher wages and/or more generous benefits to entice people to come back out into the labour market. The reasoning behind this can range from the dry and academic “This is how free markets work - people who require a resource will use high prices to signal to producers to produce more of the resource”, all the way to the practical “Duh, if you pay me enough, I’d do anything.” (and if you think about it, these two statements essentially mean the same thing, just that the former is the “big picture view”, whereas the latter is the “personal motivations” perspective).

If you are an employer, it’s perhaps reasonable to feel slightly annoyed at needing to pay more money for your employees. I mean, nobody really likes to pay more money. It may be the right thing to do (if not from the “I need to do my part to reduce inequality” point, then at least the “this means that the free market is working” way), but it might feel annoying.

Well, I can tell you that there’s an alternative - if you already do not accept that “free markets” is a good thing, either as a matter of principle, or just simply because it doesn’t align with your interests, or both, you can always try to artificially cap labour prices.

Your very questionable, but nonetheless historically factual, options

Slavery

Traditionally, probably from prehistoric times until very recently (Mauritania was the last country in the world to officially ban it in 1981), a few key people solved this problem by physically forcing people to work for little to no compensation. Thankfully, we have now all agreed that slavery is a very bad thing, and have officially banned it (but unfortunately, there are still pockets of them, e.g. child soldiers, trafficked people, etc.) But if you still insist on cheap labour, this is obviously no longer the way to go.

Legislated maximum wage caps

Well, if you are well connected with the government, and it just so happens that power is so concentrated in the hands of the government, you may have an option, because there is historical precedence for this.

In the year 1349, the Black Death killed probably nearly half of the population of Europe. And guess what, they had a labour crisis too. And this resulted in people demanding more for wages. And if you think that the resemblance is uncanny, for those of you who think that “government handouts” are causing people to not work, pay attention to the last sentence of this excerpt:

Because a great part of the people, and especially of workmen and servants, late died of the pestilence, many seeing the necessity of masters, and great scarcity of servants, will not serve unless they may receive excessive wages, and some rather willing to beg in idleness, than by labor to get their living;

And since most of the means of production then (i.e. land) was owned by people who are by definition chummy with the monarch, they got people like England’s Edward III to introduce the Ordinance of Labourers in 1349. What you see in the excerpt above is the actual introduction text to this Ordinance.

Essentially, the main points are:

It’s illegal for workers to demand and for employers to pay wages that are above pre-pandemic prices - “... take only the wages, livery, meed, or salary, which were accustomed to be given in the places where he oweth to serve, the twentieth year of our reign of England, or five or six other commone years next before.”

It’s illegal to leave your job for a better paying one - “Item, if any reaper, mower, or other workman or servant, of what estate or condition that he be, retained in any man's service, do depart from the said service without reasonable cause or license, before the term agreed, he shall have pain of imprisonment”

It’s illegal to be unemployed - “And because many sound beggars do refuse to labour so long as they can live from begging alms, giving themselves up to idleness and sins, and, at times, to robbery and other crimes-let no one, under the aforesaid pain of imprisonment presume, under colour of piety or alms to give anything to such as can very well labour, or to cherish them in their sloth, so that thus they may be compelled to labour for the necessaries of life.”

Well, would you like to know how enforceable, let alone asking about its effectiveness, this piece of legislation is? Two years later in 1351, Parliament had to properly introduce it as a legislation that was voted for in Parliament, i.e. the Statute of Labourers 1351, which essentially has the same points as the Ordinance, just that it’s more official because it’s Parliament, the “representatives of the people” (or whatever “people” meant in the 14th century), who voted for it. In 1381, large parts of England participated in the Peasants’ Revolt that resulted in Richard II (Edward III’s grandson) to phase out serfdom.

Appealing to societal values

Okay, so if legislation to cap salaries didn’t historically work, what else could you, the cold and calculated but well connected businessperson, do?

Well, you could try getting very visible leaders in society to exhort “go back to work, because it’s the patriotic thing to do!” (like what former US Labour Secretary, Elaine Chao tried to do), or say things like “Struggle is a kind of happiness. Choosing to ‘lie flat’ in the face of pressure is not only unjust but also shameful.” (as some Chinese news outlets are doing)

But, well, who knows if these efforts will work.

“But what if I still believe in the free markets?”

Here are your potential options, which once upon a time, sounded like a no-brainer. But in today’s world, they too are beginning to have elements that are questionable to some parts of society.

Outsourcing

Sure, many richer, developed countries have tried outsourcing sometimes questionable labour practices to countries with lower wages and lax labour laws. But say that most of the labour shortages are hyper-localised, like if there’s no one to drive the trucks used to bring the goods made in cheaper countries but still require transportation to the end consumer, or if there’s no one to serve you in the local cafe. Clearly, you can’t simply use the magic wand of outsourcing to solve these problems.

Robots and automation?

Since companies aren’t:

Necessarily very willing to put out bigger carrots; nor are they

Able to muster a big enough stick to force people

Therefore, the holy grail for many companies would be to increase the amount of automation in their workplaces. And the company that everyone aspires to be is Instagram, which only had 13 employees when it was sold to Facebook (now Meta) for USD 1 billion in cash and Facebook shares.

It remains to be seen if every company is able to achieve such high value to employee ratios, but nonetheless, I doubt that companies will ever stop trying to be just like Instagram. (The flip side to this is that not everyone are as talented / hardworking / productive / lucky like Instagram, hence ironically, this collective corporate aspiration creates plenty of business opportunities for software developers, management and IT consultants, which may prove to be where most of current and future jobs may be created from, because, well, the job as to be done somehow)

However, if executed properly, this leads to a bigger can of worms - if everyone’s jobs are replaced by robots, how are most people going to:

Get an income?

So that they can buy the goods and services required?

In other words, will full automation lead to the death of economies? (Nobody knows!)

“But we can’t keep doing this! What about the inflation this is causing?”

If you are someone who is concerned about inflation in general (“if we don’t nip this in the bud, then we will see inflation just like in the 1970’s! The seventies I tell you!”), then you might feel annoyed at wage inflation too. “Oh, when people demand more wages, they have more money to spend, which drives up prices for the few goods that we have, which leads to more people demanding higher wages to afford the newly jacked up prices, and this creates a vicious cycle,” you might argue.

Therefore, you may be inclined to support the idea of central banks raising interest rates. You may reason that if interest rates are higher, then people can’t afford too much credit, and therefore, people won’t spend as much, thus reducing demand pressures.

However, before we can conclude that the central bank can magically stem our latest bout of inflationary pressures by increasing interest rates soon, there are two questions that we should at least think about.

The first counter question to your inflation question is:

“But what about all this inequality? It’s got to be solved somehow!”

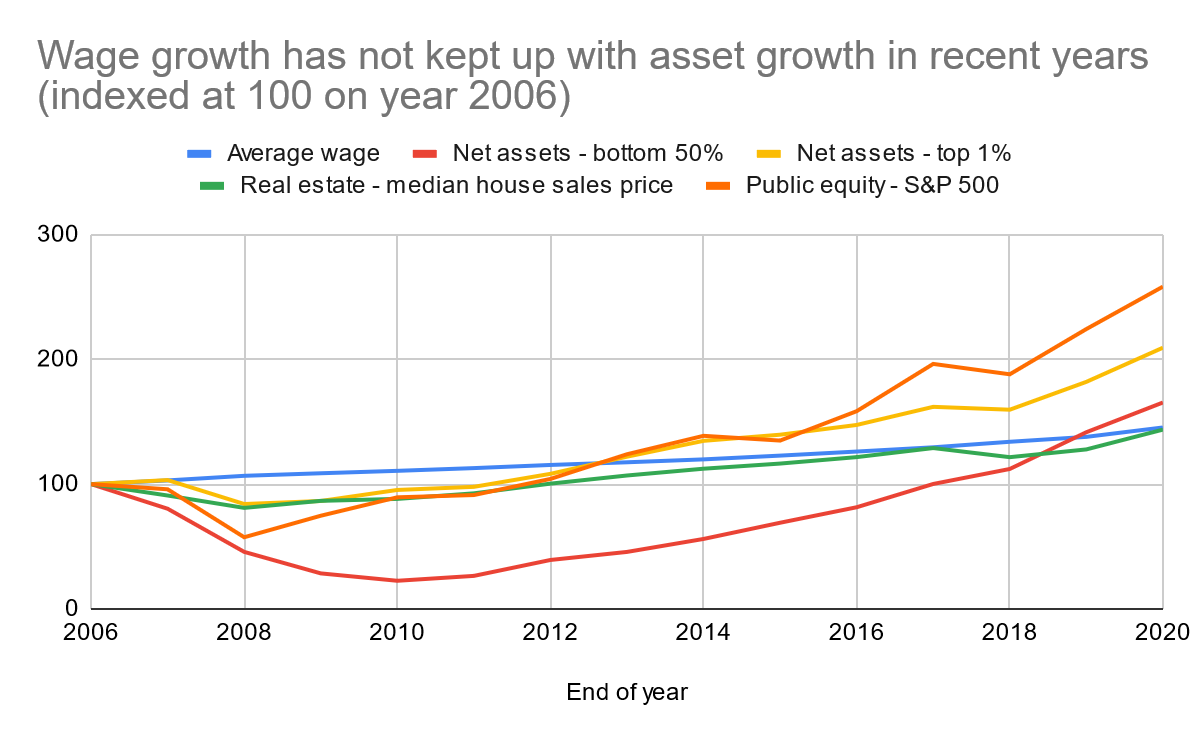

Below is a chart showing that, in the US at least, the rich are indeed getting richer a lot faster than everyone else. If you look at the net assets of the bottom 50% of the US population (red line), they have had their net worth decimated after 2006. They have only recovered after 2017, which is a good 10 years after. This is contrasted with the net assets of the top 1% of the US population (yellow line), where not only have they fully recovered by 2012, their current (end of 2020) net worth has grown so much more than the bottom 50%’s - their net worth has doubled (index value = 209) since 2006, whereas the latter’s net worth has only increased by 65% (index value = 165).

The chart below also shows that average wages have not kept up with asset value growth. For example, the S&P 500 index (our proxy for the US’s stock market) has grown to an index value of 258, whereas average wages have only grown by 45% (index value = 145). This means that if you didn’t have a lot of assets in 2006, and therefore rely a whole lot more on wages for your livelihood, you haven’t experienced the strong growth that the more asset rich people have experienced. And honestly, this must feel like you’ve been left behind, and that must feel like crap. Therefore, having these sharp wage increases today can only feel “fair” to you as you are very much overdue in sharing the spoils of a strong growing economy.

Sources: Average wage data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics; Net assets data from the US Federal Reserve; Median house sales price data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis; S&P 500 data from Yahoo Finance.

High concentration of assets may also be the cause of low interest rates

This is the second issue that people asking for central banks to raise interest rates may have to address first.

In Irving Fisher’s (the dude who brought us the “Fisher Effect”) book “The Theory of Interest”, he postulates that interest rates are merely a measurement of our impatience for future income. The postulate works as such:

If we don’t have a lot of money today to fulfill our basic needs, we may feel very anxious about our next meal, and therefore, we place a huge premium for having cash on hand (or under our mattresses, or anywhere immediately accessible). In other words, we have a high impatience for future income as we would rather have the income now, and therefore we may be more willing to borrow money at a higher interest rate.

On the other hand, if we had plenty of money today, we needn’t worry too much about having immediate access to cash. Hence, we would have a low impatience for future income, which leads to low interest rates because we don’t need to borrow as much from our future selves.

So assuming that this mechanism is true, let us try to fit this idea into our current world - if most of our global assets are owned by a small handful of individuals, they can’t possibly consume all these assets (in other words, their marginal propensity to spend isn’t high). Because they aren’t spendinging as much as a proportion of their net worth, they are:

Not as efficient on a per dollar of net worth basis, to drive consumption for goods and services that everyone else may provide (e.g. food, drinks, holidays, etc.), hence average wages in society stay lower;

Saving up all this excess “value” that they have into assets such as property, bonds and shares, which is both a driver for high asset prices therefore low interest rates (since price and interest rates or rates of return are inverse to one another).

This theory here is supported by analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City in this August 2021 paper.

The point I’m trying to make here is that while central banks can choose to increase interest rates as a matter of policy to keep inflation in check, this high concentration of assets may not make the central banks’ jobs easy at all.

So how do we square the circle?

[this section is intentionally left blank]